Tithli Ben migrated to Delhi in 1969 at the age of 19 after marriage to Dumru Bhai, a mechanic working in a small workshop in Mehrauli in South Delhi. They settled in a small juggie near the workshop. Dumru Bhai was on contract, and used to get paid based on work done. Since it was a small workshop, the orders were few and the income was low.

Within 6 months of married life, Tithli Ben realized that to survive in a metro like Delhi, the small income that Dumru Bhai earns would not be sufficient. Like other women in the neighbourhood, Tithli Ben decided to take up domestic work to supplement their income. Her hard work made her a much sought after maid, and within a year she was able to secure work in 7 houses.

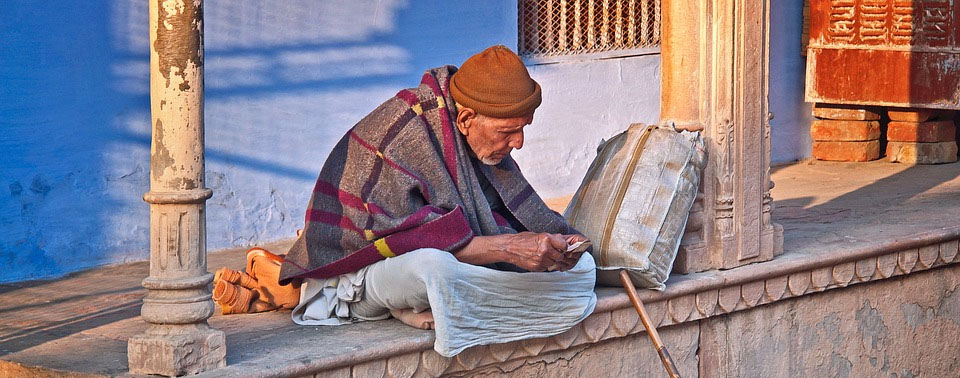

After 41 years of struggle in Delhi, Tithli Ben (now a widow and mother of five girls), continues to stay in the same old jhuggie for a monthly rent of Rs. 1250. She has married off her daughters and none of them stay with her. “They have their own burden to bear”, she says. The relentless hard work has taken its toll on her health. “I can still do work, but people prefer me less, people prefer younger hands”, says a frail looking Tithli Ben.

“How long will one live? I do not know. I was always working hard. Now I realize that old age is fast grappling me and that I might not be able to continue for long. Who will there be to support me? If I had a son, he would have been with me. Oh! That is also not true, because now-a-days who is willing to take care of their old parents?” asks Tithli Ben.

Tithli Ben feels that the government should adopt measures to protect domestic workers like her, or at least provide some solace during their old age. “If I cannot earn, I will not be able to pay the rent. If the rent is not paid, the landlord will soon have me thrown out, which means I will have to live on the pavement or at the mercy of my daughters all of whom who stay with their in-laws”, bemoans Tithli Ben.

“Why can’t the government give us some kind of pension? The plight of domestic workers are similar everywhere, but the poor and elderly are totally neglected and discriminated. Do we deserve such treatment? We have also spent our youth working really hard”, she states.

Due to lack of other opportunities, millions of women and girls take up domestic work only to support their families. But these millions of workforce are exposed to human rights abuses including denial of right to education, health, an adequate standard of living and freedom of movement. Domestic workers also face very seriously the risk of trafficking. Lack of awareness with no legal protection, makes these women workforce vulnerable to violence at their work place. Governments, across the globe, have not taken serious initiatives, even to provide the domestic workers a minimum guarantee to work with dignity.

All workers are entitled to core labour rights, including the right to wages which provide them with an adequate standard of living, reasonable working hours, the right to rest, the right to holiday, and the right to join a trade union. Understanding the rights’ violations of the domestic workers, in March 2008, the ILO governing body along with some of its supportive member states agreed upon to start the standard setting procedure for a convention on domestic work and also to have decent work for domestic workers agenda discussed during the 2010 International Labour Conference.

It seems that the need for a special ILO instrument (convention) to protect the rights of domestic workers as workers in international and national law is catching up slowly and steadily across the world. A few countries are putting in place laws to protect domestic workers rights, but a major chunk of employers and governments have not yet seen the need for an international labour standard for domestic workers and the need for pursuing it. With the concerted efforts ILO intends to take, there seems some gleam of hope for those millions of workers around the globe.

In India, in spite of the positive attitude shown by various organizations working for domestic workers, the government has not yet reflected on the issues of domestic workers or shown any positive initiative for propagating the need for such a convention. Domestic work should be given recognition as real work and domestic workers should be considered as workers.

In India, under the Unorganised Workers Social Security (UWSS) Act, 2008, people over 65 years from BPL families, are entitled to a pension (the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme) of Rs 200 per month. Taking into consideration the spiraling prices of food, medicines and a lack of social support, this pittance pension amount of Rs 200 seems to be a real shame!

Toiling hard at a very early age, millions of women like Tithli Ben turn old early and are in need of support long before they turn 60. They live in poverty and struggle to survive. Don’t you think that people like them need protection and care?